The Descent Into Abstraction Is Easy.

By Petra Bogle. For Art History 322: Radical Transformations: Modern Art 1875-1950. Grade: A+

No image is truly abstract. No such image has or ever will exist. There are degrees of abstraction, ranging from what has some representational form, and discernable meaning to the closest to true abstraction, where the elements of an image convey nothing but their own innate visual qualities, and the meaning discernable only through subsidiary material. Every successive generation of artists have found new ways to imbue images with meaning, and ways to divorce meaning from the physical qualities of the image. Auguste Rodin (1840-1917) began by whittling the human form, severing limbs and heads, roughening the texture of what remained, in poses that would never be assumed by an actual person. Pablo Picasso (1881-1973) toyed with the medium of sculpture, exploring its capacity to extol what he saw as the underlying science of the world. Constantin Brâncusi (1876-1957) simplified the world to a more basic level, using titles to signal the meanings of his works. Naum Gabo (1890-1977) came closest to complete abstraction, creating works which almost purely depict only their physical qualities.

The form of Rodin’s sculpture is characterized by strained naturalism. This can be viewed as slight abstraction, which he employed due to his concerns as a sculptor that sculpture was overplayed and inaccessible. For example, in The Walking Man (1877) (Fig. 1) does not have a traditional geometric form, instead Rodin places the figure on top of an undulating form. This has the effect of bringing the sculpture closer to the viewer.[1] Contributing to a sense of movement in the otherwise static work is the way that the base rises up underneath the left foot. Albert Elsen likens it to a launching pad.[2] This comprises a rare interaction between the usually static base and what is typically accepted as the actual subject. While this in itself is not an act of abstraction as we would now think of it, such choices are very slight movements towards overall abstraction.

The pose of The Walking Man is also somewhat abstract, lacking a number of naturalistic elements. The most obvious is the absence of both arms and head, with Rodin including only the torso and legs. The feet are placed flat against the ground, facing in the opposite direction to the body. The entire figure is awkward. If assumed, the pose is highly uncomfortable and abnormal. The back leg is longer than the front one. Elsen argues that the idea of movement nevertheless remains plausible, and that Rodin contrived the figure awkwardly to create a more convincing sense of movement.[3] The figure is splayed upon the base, and looks more likely to topple over than swing through for another step. The advent of photography contributed to the rise of abstraction in art. Photographs made such naturalistic pursuits superfluous, and thus it follows that artists began to abstract as the demands of naturalistic representation were met.

According to Elsen, Rodin was uninterested in capturing human movement in sculpture.[4] Instead Rodin’s interest in reading a work from multiple perspectives is captured in this work, in that as the figure “walking” does not make logical sense, it must be read as the “metamorphosis of the first gesture.”[5] In other words, perhaps that movement begins with the body, or a part of the body such as the legs and feet. In an interview with the critic Paul Gsell, Rodin explained for example you could read it as movement flowing from the turned out backward foot, through the body into the front foot.[6] The strained nature of the pose is integral to the sculpture’s abstraction.[7] By both feet remaining affixed to the ground, Rodin is able to show this succession of movement, while contradicting the photographic evidence of what a walking man truly looks like to the human eye. This disconnect between the observable reality, the artistic representation of that reality, and the concept underpinning it makes this work abstracted. However, while it is confusing and contradictory a higher degree of abstraction is precluded by the fact that it remains fundamentally recognizable. Each choice is in itself fairly insignificant, but in conjunction and comparison to contemporary sculpture it becomes abstracted.

Picasso created images with a greater level of abstraction than Rodin. One of the key aims of Picasso was to depart from naturalistic representation of form. An early painting Girl with a Mandolin ‘Fanny Tellier’ (1910) (Fig. 2) shows this tendency. A mass of geometric forms make up the image of the subject with her mandolin. As a result, both the picture plane and any naturalistic sense of space and perspective is disturbed. Picasso’s sculpture also dispenses with conventional form. He made a number of sculptures of guitars, such as Guitar (1914) (Fig. 3). This is an image of an everyday object depicted in an unfamiliar manner. It is an assemblage work, that in itself a revolutionary concept of the time.[8] By piecing together flattened metal, Picasso is able to suggest the outline of the 3D guitar, by delineating it with 2D sheets. The volume of the work is merely suggested. Picasso directly contradicts our expectations of a guitar, as the sound hole projects outward rather than inward. Both the above sculpture and painting show that it is clear that true to life representation is not Picasso’s priority. Instead through partial abstraction, he is suggesting additional meaning as well as the outward depicted subject matter. Such meaning can be gleaned by viewing other works, or reading about the Cubist rationale.

Brâncusi approaches abstraction of form very differently to both Rodin and Picasso. Unlike Picasso, his work shows his focus on simplification of all aspects of life, to its most essential form.[9] Brâncusi worked as an apprentice to Rodin in the early years of his time in Paris, but left after only a short time, declaring later that “nothing grows in the shadow of great trees.”[10] His interest in simplicity is illustrated in works such as Bird in Flight (1932-40) (Fig. 4), which captures the idea of flight, rather than depicting it overtly. His work bears similarity to Rodin’s in the suggestion of movement. The curve of the form alone suggests the only the most basic element of flight. It does not show a beak, or the shape of the bird, or its claws. But would a viewer, without reading the title be able to understand this idea of flight from the work? It seems that for works like this, and many others of Brâncusi, the title plays a vital role in signposting the meaning of the work. Therefore, has the work itself reached the highest possible level of abstraction? Perhaps it would be a mere form with a particular shape if it were untitled.

Of the four artists discussed, Gabo comes the closest to achieving true abstraction, or works that are fully abstract. They seemingly reference nothing but themselves, their materials stand on their own. While some claim they are free of symbolic value, it could well be argued that they uphold Gabo’s ideas, and thus do hold symbolic value. Gabo’s ideas on the future of sculpture, and role of art were set out in his “Realistic Manifesto”:

“Space and time are the only forms on which life is built and hence art must be constructed…as the universe constructs its own, as the engineer constructs his bridge, as the mathematician his formula of the orbits…We affirm the line only as a direction of the static forces and their rhythms in objects.[11]”

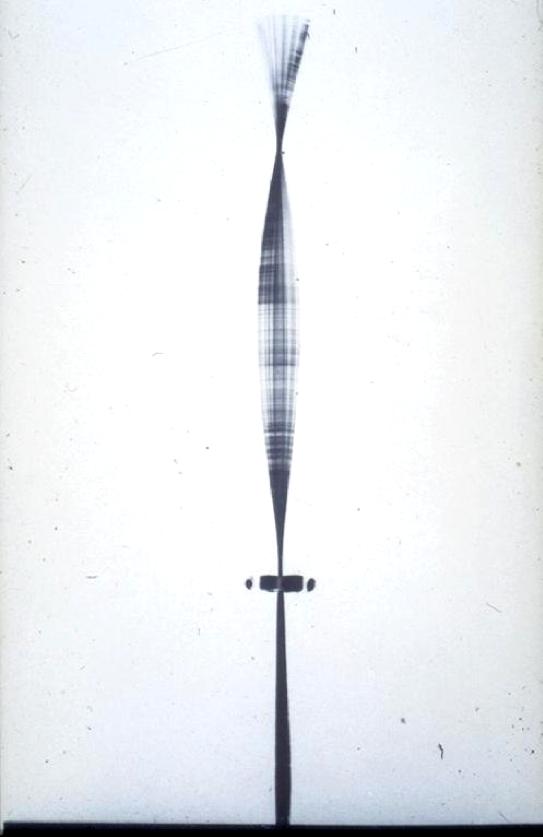

Linear Construction No. 4 (1962) (Fig. 5) embodies this rejection of solid form, the wires crisscrossing between the spheres of metal serving to designate volume without filling it. Instead of creating forms which weigh on and occupy space, Gabo uses the wires to create a sculpture that “reveals the continuity and tangibility of space.”[12] He embraces the negative space areas created by the gaps. Gabo believed that mass was not the most fundamental aspect of sculpture in general. It was one of two fundamentals, the other being the volume of space that it created by a work. Works such as Kinetic Construction (Standing Wave) (1919-1920) (Fig. 6) illustrate this. It creates a virtual volumetric zone, where the rod moves producing an optical illusion. The lighting and the time that the rod takes to vibrate are the elements which create a volume of mass in space, thus uniting the two fundamentals of sculpture as Gabo saw them. All this shows Gabo’s basic interest in form, how it could be manipulated, and what happened in the absence of physical form. His construction method also shows how he built his sculptures from the most basic of geometric forms. Despite this basic simplicity his work is undeniably the most abstracted. There is almost complete separation from the physical work and what it purports to depict. Nevertheless, it is not the theoretical endpoint of abstraction.

True abstraction is the absence of meaning, and the human mind is unable to comprehend any object without ascribing meaning to it. A square is a square, which is a shape, which is a block to one mind, and a collection of lines to another. But in all minds it means something. There is nothing controversial in claiming that every existing object has the capacity to carry meaning. Rodin began by making small departures from naturalism, and each sculptor who followed owes this first step to him. His abstraction emerged as a result of his disillusionment with traditional sculpture, as he explored to find an alternative in form. Picasso utilized abstraction to explore the theories of science which he believed, to disrupt the form but not dispense with representation entirely. Brâncusi found representational naturalism far too complicated to illustrate the essence of the world, so chose to limit himself to basic forms. Similarly, Gabo had no interested in realistic representation of form, so he abstracted form at times to a point where it was unrecognizable as anything other than what it physically appeared to be. But none of these artists could bear to allow their works to go untitled, or could stop themselves preaching their ideology to the world, through manifestos or interviews. As a result, meaning could always be attached to their works no matter how confusing the form. Certainly, Gabo is the most abstract artist. His work is the hardest to understand in terms other than its physicality. Brâncusi’s work utilizes form that is similarly irascible. Picasso and Rodin were the trailblazers; their work is only moderately abstract. A truly abstract work would be incapable of conveying meaning. It is my view that the human mind is not able to comprehend the theoretical end of the scale of abstraction.

[1] Albert Elsen, “Rodin’s “The Walking Man”.” The Massachusetts Review 7, no. 2 (1966): p. 290.

[2] Elsen, “The Walking Man,” 292.

[3] Elsen, “The Walking Man,” 292.

[4] Elsen, “The Walking Man,” 290.

[5] Albert Elsen, “Rodin’s “The Walking Man”.” The Massachusetts Review 7, no. 2 (1966): p. 290.

[6] Elsen, “The Walking Man,” p.291.

[7] Norbert Lynton, ‘Expressionism,’ in ed. N. Stangos, ed., Concepts of Modern Art, (New York, 1994), p.33.

[8] Christine Poggi. “Picasso’s First Constructed Sculpture: A Tale of Two Guitars.” The Art Bulletin 94, no. 2 (2012): p.274.

[9] Margherita Andreotti. “Brancusi’s “Golden Bird”: A New Species of Modern Sculpture.” Art Institute of Chicago Museum Studies 19, no. 2 (1993): p.138.

[10] Andreotti. “Brancusi’s “Golden Bird”’, p.137.

[11] Susanne F. Hilberry “Naum Gabo, A Constructivist Sculptor.” Bulletin of the Detroit Institute of Arts 54, no. 4 (1976): p.177.

[12] Hilberry “Naum Gabo, A Constructivist Sculptor.” p.178.

Bibliography:

Abell, Walter. “Form Through Representation.” The American Magazine of Art 29, no. 5 (1936): 303-10. http://www.jstor.org.ezproxy.auckland.ac.nz/stable/23940878.

Andreotti, Margherita, and Brancusi. “Brancusi’s “Golden Bird”: A New Species of Modern Sculpture.” Art Institute of Chicago Museum Studies 19, no. 2 (1993): 135-203. doi:10.2307/4108737.

Elliott, Patrick. “Picasso’s Sculpture. Paris.” The Burlington Magazine 142, no. 1171 (2000): 649-52. http://www.jstor.org.ezproxy.auckland.ac.nz/stable/888924.

Elsen, Albert. “Rodin’s “The Walking Man”.” The Massachusetts Review 7, no. 2 (1966): 289-320. http://www.jstor.org.ezproxy.auckland.ac.nz/stable/25087428.

Hilberry, Susanne F. “Naum Gabo. A Constructivist Sculptor.” Bulletin of the Detroit Institute of Arts 54, no. 4 (1976): 174-83. http://www.jstor.org.ezproxy.auckland.ac.nz/stable/41504577.

Poggi, Christine. “Picasso’s First Constructed Sculpture: A Tale of Two Guitars.” The Art Bulletin 94, no. 2 (2012): 274-98. http://www.jstor.org.ezproxy.auckland.ac.nz/stable/23268315.

Stangos, N., Concepts of Modern Art. New York, 1994.